MA Estate Tax in 2019 | Worst Estate Tax or Best at Redistributing Wealth?

At $1 million, Massachusetts is in a dead heat for the lowest estate tax threshold in the country. That means anyone worth more than that at death is contributing to the tax coffers. Depending on your point of view, that’s just life (or death) in the big city, tragic, or possibly progressive.

What are estate taxes and how are they determined?

There is much confusion around estate taxes. Even the name is confusing: One can’t tell at first if the tax is on income or assets of the estate. The short answer is that estate tax applies to the assets of the estate, but how it is calculated and who has to pay is often far from clear.

A taxable estate is made up of the assets of the deceased person in any shape or form. The assets may pass through probateProbate can refer to the process of settling the estate of a deceased person. Read More court or through trusts, or pass to a surviving joint owner. Others, like IRAs, annuities, and life insurance are paid to beneficiaries. All of these assets make up the “taxable estate” and may be subject to estate tax on the total value of the items. The government has a lien (like an attachment) against all real property in an estate with few exceptions. Thus, if you do not pay the tax, the government can foreclose the lien or collect when you sell.

Estate taxes are a levy on the fixed value of the estate as of the date of death. Federal estate taxes and several state estate taxes may apply if your estate exceeds the applicable exemption amounts, after taking any available deductions.

The estate tax captures revenue for the government that it might never see otherwise. Without a tax on inheritances, pent up earnings never get taxed – at least not until the underlying wealth gets sold, which may not be for a long time, perhaps generations.

Estate and trust income tax, on the other hand, such as interest, dividends, capital gains, and rent are taxed annually with returns due April 15 like for most other income taxes.

What are the current exemption amounts?

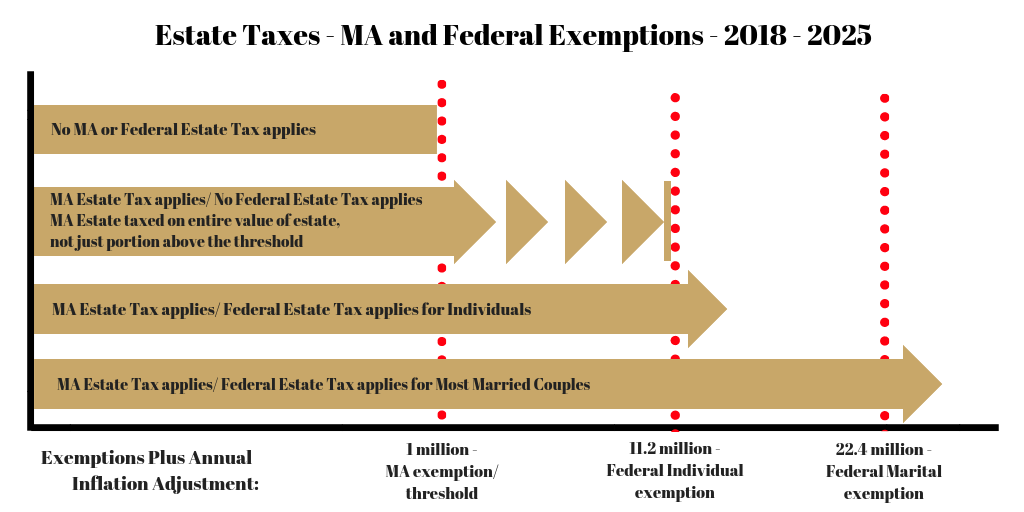

The 2019 Massachusetts estate tax exemption is $1 million. Estates with a net value of more than this pay an estate tax as high as 16%.

The federal estate taxFederal Estate Tax: The federal estate is part of a unified federal gift and estate tax that is an excise on the transfer of wealth. Read More exemption is at a historic high in 2019 of $11.4 million for individuals ($22.8m for couples). Break that threshold and your heirs are liable at a flat rate of 40% of the amount over the exemption.

Democrats in Congress propose to lower the federal exemption to $3.5 million. Even without a change anytime soon, the current law will “sunset,” reducing the exemption to an estimated $6 million ($12 million per couple) by 2026, still with a 40% flat rate.

Planning to maximize exemptions and deductions

There are three big breaks available against estate taxes: the maritalThe provision of the US Tax Law that allows the estate of a decedent to take a deduction equal to 100% of the value of assets passing to the surviving spouse or that qualify for the QTIP election. Read More deduction, the exemption amount, and the charitable deduction.

Both federal and Massachusetts estate tax codes have an unlimited maritalThe provision of the US Tax Law that allows the estate of a decedent to take a deduction equal to 100% of the value of assets passing to the surviving spouse or that qualify for the QTIP election. Read More deduction. This means that any asset passing exclusively to the surviving spouse is not subject to estate tax. But note: the maritalThe provision of the US Tax Law that allows the estate of a decedent to take a deduction equal to 100% of the value of assets passing to the surviving spouse or that qualify for the QTIP election. Read More deduction only defers taxes; it does not eliminate them. If the property remains in the surviving spouse’s estate, it will be taxed at his or her death.

What assets earn the marital deduction?

Any part of the estate that passes exclusively to the surviving spouse will earn the maritalThe provision of the US Tax Law that allows the estate of a decedent to take a deduction equal to 100% of the value of assets passing to the surviving spouse or that qualify for the QTIP election. Read More deduction. The surviving spouse may become the owner or sole beneficiary of an asset – the home, an account, or IRA – and as such earns the maritalThe provision of the US Tax Law that allows the estate of a decedent to take a deduction equal to 100% of the value of assets passing to the surviving spouse or that qualify for the QTIP election. Read More deduction for these assets. The spouse may be the beneficiary of a trust, but to qualify for the maritalThe provision of the US Tax Law that allows the estate of a decedent to take a deduction equal to 100% of the value of assets passing to the surviving spouse or that qualify for the QTIP election. Read More deduction, the spouse must be the sole beneficiary during his or her life. The trust must pay the spouse, and the spouse alone, all of the income produced by the trust. If the trust meets these tests, it qualifies for the deduction.

Using the full exemption

You might think that it makes sense to leave the whole estate to your spouse because that way it is exempt from tax, but in states that have an estate tax, and even in most federally taxable situations, it makes more sense to allocate the exempt amount when the first spouse dies to a trust for the survivor. In contrast, if the entire estate is left to the surviving spouse, the deceased spouse’s lifetime exemption is lost in most states and is locked, never to appreciate in value for federal purposes. Careful planning is required so that you do not saddle the surviving spouse with too large an estate, with only their own, single lifetime exemption left.

We estate planners love bringing the value of the estate below the estate tax threshold – federal or state. It’s sort of a game to “win” the no-tax challenge through a combination of – often flashy – trust, gift, and entity techniques. With modest estates eliminating the tax can be done with sensible gifting, often using “gift trusts” that do not actually put funds into heirs hands until after the client’s death.

How charitable deduction factor in

This deduction, as the name suggests, is for the part of the estate given to qualified charities. Some wealthy clients have been known to give the large federal exemption amount to their family members and the entire estate over the exemption amount to charity, thus being generous with both family and charity while paying the government zero.

We evaluate whether the estate or the heirs will benefit more from the charitable deduction. With a state tax of, say, 10% and personal income tax rates in some cases at 43%, it is easy to see how that calculation comes out in favor of having the heirs pay an estate tax and then personally donate to charity, earning a much better deduction on their income tax than they would get on estate tax.

Even if no tax is due, filing is required in order to take advantage of the maritalThe provision of the US Tax Law that allows the estate of a decedent to take a deduction equal to 100% of the value of assets passing to the surviving spouse or that qualify for the QTIP election. Read More or charitable deductionsIn estate and gift tax, 100% of what is given to qualified charities is exempt from tax. “Qualified’ means recognized by the IRS. and the exemption amount.

What needs to be filed?

For your estate income tax preparation, 1099s and W-2s and K-1s are needed.

For estate tax preparation, appraisals, complete statements of accounts, life insurance form 712s, and lots of legal documents are needed.

The schedules of the return require the compilation of all assets owned by or in which the decedent had an interest, or for which a trust was created at death. Assets over which the decedent had legal power to direct (“power of appointment”) need to be listed as well, even if the decedent didn’t own them. Why you wonder? This is the government’s way of sniffing around to make sure all assets are identified.

The federal estate taxFederal Estate Tax: The federal estate is part of a unified federal gift and estate tax that is an excise on the transfer of wealth. Read More return will include past significant gifts made by the deceased person. These so-called “taxable gifts” were those in excess of the annual exclusion from gift tax ($10-15,000/per person/per year in recent memory). These large gifts reduce the exemption from federal tax. Your Massachusetts return will not account for gifts because there is no state gift tax in Massachusetts upon death.

The federal tax returns also report when special past exemptions were taken, such as the generation skippingTrusts that may be direct gifts to beneficiaries two generations below the Grantors, or that may provide discretionary benefit to the next generation with the possibility of preservation until the following generation. Read More transfer tax and the deceased spouse unused exemption allowance (“DSUEA” – the amount left over of the federal exemption that is not used by the deceased spouse).

Estate documents such as wills, trusts, and deeds must also be attached. These documents require careful reading for implications regarding estate tax and deductions. To this, add valuations and in some cases legal or accounting opinions.

You should never feel complacent about your filing until you get either a “closing letter” from the government or can check your account to see that they have agreed the balance due is zero.

When is the return due?

Estate tax returns are due nine months after death, but they can also be extended by filing for an extension with the department of revenue or IRS. There is no penalty for an extension provided either there’s no tax due or an accurate estimated payment is made, ahead of time.

In our experience the typical estate tax return will consume at least 15 hours of preparation. Additional services for review or preparation of documents, appraisals, disclaimers, and schedules will add time. The number of holdings and the complexity of the holdings, trusts, companies, etc. all contribute to the time invested in the return.

Why do we have an estate tax, anyway?

Love it or hate it, the estate tax has been around since 1916 in one version or another. President Theodore Roosevelt thought an inheritance tax was a good idea, though the popular Rough Rider couldn’t get it passed. Andrew Carnegie was an early proponent who helped push it through in 1916. The philanthropist believed that the tax was a check on the “aristocracy” in America. He correctly pointed out that the heirs of the rich got richer, not through their industry, but because their inherited wealth – stocks, bonds, real estate, and business interests – grew and was never taxed.

The haters of the estate tax see it as a crude tool for the government to get revenue: It doesn’t discriminate between those assets that are worth only what you paid for them or that have dropped in value, and those that have appreciated, or that were taxed in the previous generation’s estate already. The tax can hurt farmers and small businesses in many cases because in order to pay the tax, enterprises need to be broken up or sold. That’s not good for business!

There have always been those who think taxes should be one-and-done when it comes to taxing our stuff. Their point is that they (or someone) already paid a tax on the earnings that produced the asset. “You’re adding insult to injury” by taxing it again at death, goes the argument.

The future of the estate tax

One hundred years later, the federal tax is still around. But only about 1 in every 1,000 Americans will pay. This could change. Only a few years ago it was more like 1 in 100.

With federal income taxes at historic lows and with high budget deficits, some would like to see a stiffer estate tax, one that could bring in billions off of accumulated wealth in America.

Alternatives to the estate tax are available: increased capital gains taxes when inherited assets are sold, or imputing sales on assets held beyond a fixed period of years. Changing rules on charitable tax breaks might also result in more tax revenue and cause the largest philanthropies to dole out their money for good causes faster.

In the other states where we practice: New Hampshire has no estate tax. Rhode Island taxes estates above $1.562 million and New York above $5.7 million. Both states index for inflation. Florida (where we are not admitted), the home to many clients in retirement, also has no estate tax. Here is a chart of the 50 states and the District of Columbia with details on the taxes on estates.

Massachusetts shows no sign of changing its tax. Meanwhile planning opportunities present themselves on a daily basis.

Ask about your unique situation by scheduling a complimentary call with our experienced paralegal Paula.